The impact of COVID19 has caused changes and chaos for most of us across the world, whether we have gotten sick or know someone who has, or whether we have made significant lifestyle changes to help “flatten the curve”. We have learned about how viruses multiply exponentially, witnessed the shutting down of schools and businesses, and watched as hospitals filled and protective equipment ran out. But we have also seen creativity in connection, enjoyed the slowing down of our busy lives, and refocused on being present with our own families.

In neuroscience, it’s the “mammal brain”, or higher brain, that turns you toward your caregivers when you are in danger. This is the pull toward “home”, whether it is your own parents or chosen family. This is why children - whether ours or those we teach or love - turn towards us for learning how to handle a crisis, how to regulate our emotions, and how to feel about all that is going on in the world around us.

It is the “reptile brain”, or lower brain, that tells us to run from danger. That’s what helps us remember to wash our hands. That’s what makes us strong enough to stay away from neighbors and friends and family that we miss during social distancing. That’s what cringes inside us when we hear stories of people being exposed, getting sick, or so many people dying.

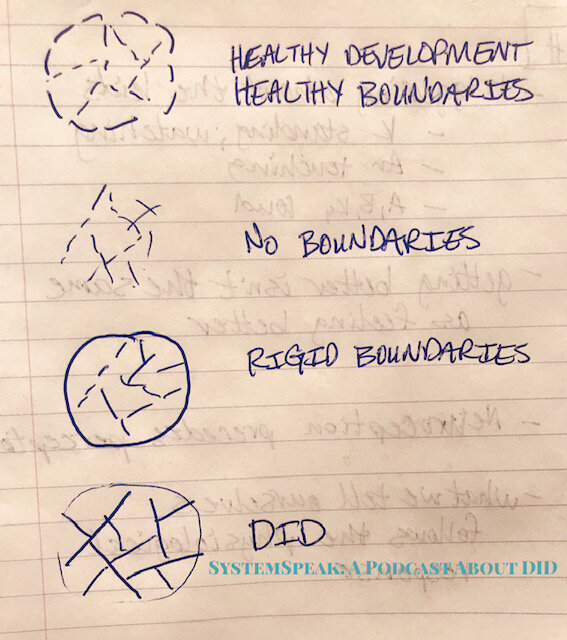

There are times in life when the brain gets both signals at once, causing a conflict that makes it feel impossible to respond. For example, with child abuse, the brain wants to turn toward the caregiver for safety. But the brain also wants to run away from the caregiver who is causing the danger. And yet the brain knows the body is dependent on the caregiver to stay alive because they are only a child, despite the danger that is also present.

That is trauma - not just when you get hurt physically, but when external situations leave no way to get out of what is causing danger, but also no protection from that danger.

To make things even more challenging, your brain itself doesn’t actually perceive context. It just knows signals it receives from your body and the chemicals rushing through your body. So sometimes even the experience of this dynamic, either relationally (with others) or only the perception of danger, is enough to tell your brain that you are in danger and initiate a trauma response.

When your brain gets the signal that you are in danger, one of the things it does is send a message to the vegus nerve, which goes from your brain to all your major organs (heart, lungs, etc.). Because it branches off along the way, it is called the “polyvagal nerve”. This is what prepares your body to respond to danger.

When your trauma response is activated, the polyvagal nerve presses down on your organs so that you are ready to respond to danger. You can’t detect danger and then decide to respond and then tell your body to get ready for it. For survival, your body has to already be ready to respond to danger as soon as it is detected.

When you are not in danger, it means you are feeling safe and you others around you also feel safe. Your brain knows this through tone of voice, content and rhythm and pacing of conversation, and facial expressions. Your body matches these as part of safe mode: your affect is brighter, and your voice is modulated (goes up and down in pitch), and so you feel calm and good and happy.

But when you feel there is some danger, or your body senses it, then the nerve is activated against your organs, so as to prepare your body to respond to that danger. Your body doesn't have to be in actual danger - it might just be perceived danger - even just another person's facial expressions or tone of voice can be perceived as danger. Then your own facial expression goes flat, and your voice goes more monotone, and your heart and lungs are pumping in preparation for "flight". This often is where panic attacks happen.

If you aren't able to feel safe again quickly, and you still feel in danger, then your body thinks now your life is being threatened (whether it is or not), and you drop down another stage into "fight". Because you couldn't get away from the situation, now your body wants to fight. This is when verbal aggression increases, or you feel then tightness in your arms and legs instead of just your chest.

When you can't win at fighting, even if it's just with someone who argues better or differently than you do - even if that's not oppressive or even abusive - then your body goes into shutdown mode, or “freeze”. Your mind goes blank. You basically dissociate. You don't respond to anything.

Falling down that "ladder" - from safety to flight to fight to shutdown - always happens in that order, though some stages may happen more quickly than others for some people. And to get back to safety, you have to go back up the ladder in the same order you came down - so back up to fight (being willing to confront a situation or something you were avoiding or something you need to try or do differently) and then up to flight (getting away from what isn't healthy, what isn't safe, what patterns are not positive or beneficial for you) until you get back up to safety.

Right now, with the COVID19 experience globally, we as individuals (and as communities) are experiencing a trauma response. There is no way you can actively “fight” the actual virus itself, and there is no way to get away from the experience of the pandemic (“flight”). It impacts us in every area of our lives, and has impacted all of the people around us. No one is “safe”, and everyone around us is also responding to the same experience. Our brain literally steps down into the “freeze” response.

It is important to remember that all of your feelings are valid as you adjust to all of this and feel the impact of it in many ways. Everything you feel is okay, and all of your feelings are normal. It makes sense why you are responding the way that you are.

You may feel more tired, slow, or less motivated while in the “freeze” response. It may be difficult to focus, pay attention to others, or complete tasks. You may be hypervigilant in other ways, like staring at patterns of tile in the bathroom or at light dancing on leaves outside. You may struggle to focus on conversation, tolerate the noise of children, or stick to any kind of routine. You may feel pulled down by gravity, struggle to smile, or forget to laugh. Time may get slippery, the days blur together, and hours disappear. You may feel less real, or like you are watching yourself, or like the world around you is unbelievable.

The word for all of this is “dissociation”, which is a continuum of the “freeze” response.

You may also experience some grief responses for your loss of normalcy, the loss of your routine, and especially loss of contact with friends. You may also miss the ease with which things were accessible while still taken for granted. You may crave the earlier stability you experienced from your work or other routines. You may feel at a loss without the validation that you are busy enough, doing enough, or productive enough.

But you are enough.

What you are experiencing is a trauma response: flight, fight, or freeze.

With COVID19, that "fight" could look like anything from irritability to an increase in bickering with children or arguing with adults to actual aggression. "Flight" could look like avoidance behaviors, such as scrolling on social media for hours at a time, eating too much of unhealthy foods instead of keeping things balanced, too much screen time instead of using some of the time to organize or clean while you have the chance, isolating in your bed instead of interacting with others who live with you, or disengaging from family and friends instead of finding creative ways to connect.

"Freeze", then, could look like staying under the covers instead of being able to get up for your day, feeling sleepy or lethargic, staring into space for long periods, or needing extra sleep, or being overwhelmed with tasks as you try to work from home, or if you are still having to "go" to work, or if you are having to help children learn from home.

There are others as well, which may be more your style, besides just the common fight, flight, or freeze:

“Fawning” is when we try hard to be very good, so that we are not caught or blend in or fly under the radar. This is a very common way for children with relational trauma to behave so as not to upset the parent. It also happens frequently in domestic violence situations. With COVID19, it may look like too much handwashing or overly isolating indoors, in cases where you are properly socially distanced and can relax some in your own home.

(The above “F’s” of fight, flight, and freeze, were identified and written about by Peter Walker. The additional F’s below were identified by and written about by trauma survivor and life coach “The Crisses”. Others have come up with more, as well. We apply these here as part of educating about and sharing our own trauma responses to COVID19 on the podcast.)

“Following” is what happens when you go along with things despite the danger. In abuse situations, it looks like doing what the abuser says to do in hopes that joining with them will keep you safe. In COVID19, it looks like people who minimize the danger and refuse to self-quarantine, in effort to avoid feelings of anxiety or admit their own fears.

“Fortifying” is when we make our “walls” higher and stronger to defend ourselves better than before. In abuse survivors, this may look like disruption in relationships or increase in dissociative symptoms. It can look like social disconnect instead of social distance. With COVID19, it could be hoarding toilet paper or stockpiling medications with no evidence to actually treat the virus.

“Fabricating” is when the story is changed so it’s not scary. This is a kind of denial more than it is an attempt to actually deceive, though deception is what happens by default. In abuse situations, this could look like a child making up happy stories about their parents. In domestic violence experiences, it is telling yourself someone loves you despite the pattern of them hurting you. With COVID19, it shows up when recommendations from doctors and scientists are dismissed or downplayed.

None of these are "bad" or "wrong". They are trauma responses. Your brain is literally trying to catch up the processing of what is happening to you. Remember that your brain does not know context. It only knows the signals it receives and the chemicals flowing through, which right now is a lot of stress information with so many changes as we protect ourselves from a virus we can't actually "see" (or fight or get away from right now). Your brain may interpret that as "danger", without understanding you are doing everything you can to be safe and to continue functioning.

Feel all there is to feel. Let it come up. Notice it. Acknowledge it.

But then let it go.

You have the power to choose your response and which thoughts to dwell on and which experiences to create for yourself.

All of your feelings are valid, but your feelings are not reality. They only give you information about what is happening in reality. Receive the information, but then empower yourself to choose your response.

“Facilitating” is a way of coping that empowers yourself for positive change and healing, even if in little ways. This almost always happens in connections with others, through attunement experiences where your emotional needs are noticed, reflected and met by safe people around you. Any step towards this counts, whether it is telling the truth about abuse (they are not your secrets to have to keep), or unsubscribing from the toxic issues of others, or not taking the bait in negative thoughts in yourself or negative interactions with others.

Be gentle with yourself. Give yourself breaks. Let your body rest. You may literally be exhausted from the trauma response happening in your body, even if you are not sick at all.

Connect with others in the ways you can. Be both safe and creative in how you do. But do it.

Do deep, slow breathing periodically to help that polyvagal nerve come off your organs and remind your brain that you are safe. Regular practice of progressive muscle relaxation would also help reinforce those signals to your brain, so that it knows you are safe and aware of the situation. These very simple things that almost seem too silly make a huge difference for your brain.

Find ways to laugh and smile. You have to do it intentionally until your brain knows you are safe. But the more you smile and brighten your affect, the safer people around you will also feel. Then they will start smiling, too, and feel better themselves, which also helps you feel better as your brain notices that. Smiling makes a physiological difference, I promise.

It makes sense you feel like you have fallen down a ladder, because you have.

But you also still have the power to climb back up again.

We work online with clients internationally, as well as those living in Oklahoma, Kansas, and New Jersey.

CLICK HERE to register.